Scientists from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore have identified the world’s longest known earthquake. The so-called “slow slide” off the coast of Sumatra may have begun in 1829 before culminating in a major catastrophe 32 years later. A research paper published in Nature Geoscience discovered the link between a decades-long event and a powerful 8.5-magnitude earthquake in 1861.

An earthquake in 1861 erupted along the mighty Sundra River – the fault line east of Sumatra – and caused a devastating tsunami.

The tsunami is believed to have struck more than 300 miles (500 km) from the coast, killing several thousand people.

The tremors were felt as far as Malaysia, and the aftershocks continued to shake the area for another seven months.

By identifying a possible source of the disaster, scientists want to help detect dangerous earthquakes in the future.

Read more: Hawaiian volcano warning: An earthquake occurred under the Kolawea volcano

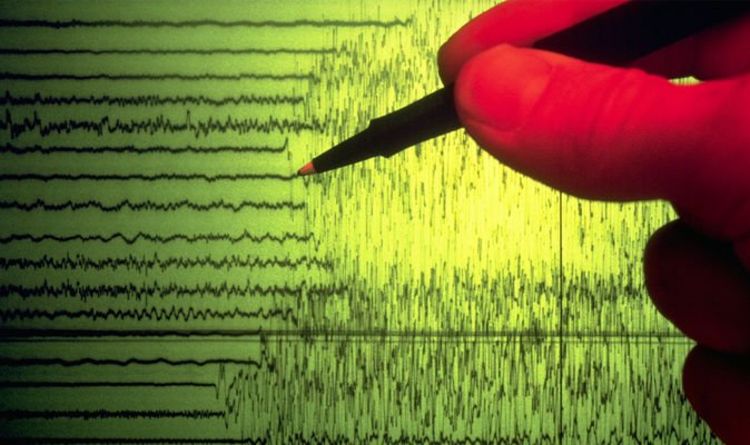

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the phenomenon of slow slip is sometimes called “slow earthquakes.”

The tremor begins when the fault line begins to slip – as with a normal earthquake – but at a slow pace.

Earthquakes can last for days instead of seconds, but a new study shows they can last much longer.

Slow slip events are often recorded at Kilauea, which is the most active of the five volcanoes that make up the Big Island of Hawaii.

A US geological survey concluded that “slow earthquakes do not cause any seismic waves and therefore do not cause any destructive tremors typical of earthquakes.

The reefs observed near Simeulue appear to show a repeated history of movement along the rift between 1738 and 1861.

About 90 years ago, coral reefs showed that the land was declining at a very constant rate of 1 to 2 mm per year.

Sometime around 1982, a sudden change in seismic activity caused the reefs to sink seven times faster—there was a slow slide.

But that all changed in 1861 when a major earthquake altered the sinking’s condition once again.

A slow slip could be the catalyst or trigger for an 8.5-magnitude earthquake.

Reshav Malik, a doctoral student and lead author of the study, told Scientific American that the earthquakes may have caused some tension along one part of the fault, but imposed more pressure on another part.

He said: It is like a bundle of springs. If one of them leaves, the others have to bear the burden.

According to the US Geological Survey, the 7.1-magnitude earthquake in Anchorage, Alaska, could be caused by a combination of seismic events, including a slow slide.

In an article published in Geophysical Research Letters, the study authors wrote: “The earthquake was favored due to the accumulation of slow-slip stresses at the surface separating the plate from the North American plate.

“The slow slip also doubled the number of M3 earthquakes at Cook Inlet that began in the 1990s.”

“Music fanatic. Professional problem solving. Reader. Award-winning TV Ninja”.

“Music specialist. Pop culture trailblazer. Problem solver. Internet advocate.”